Smith Meadows • Shenandoah Valley • Berryville, Virginia

“Land, then, is not merely soil; it is a fountain of energy flowing through a circuit of soils, plants, and animals.” — Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac, 1949

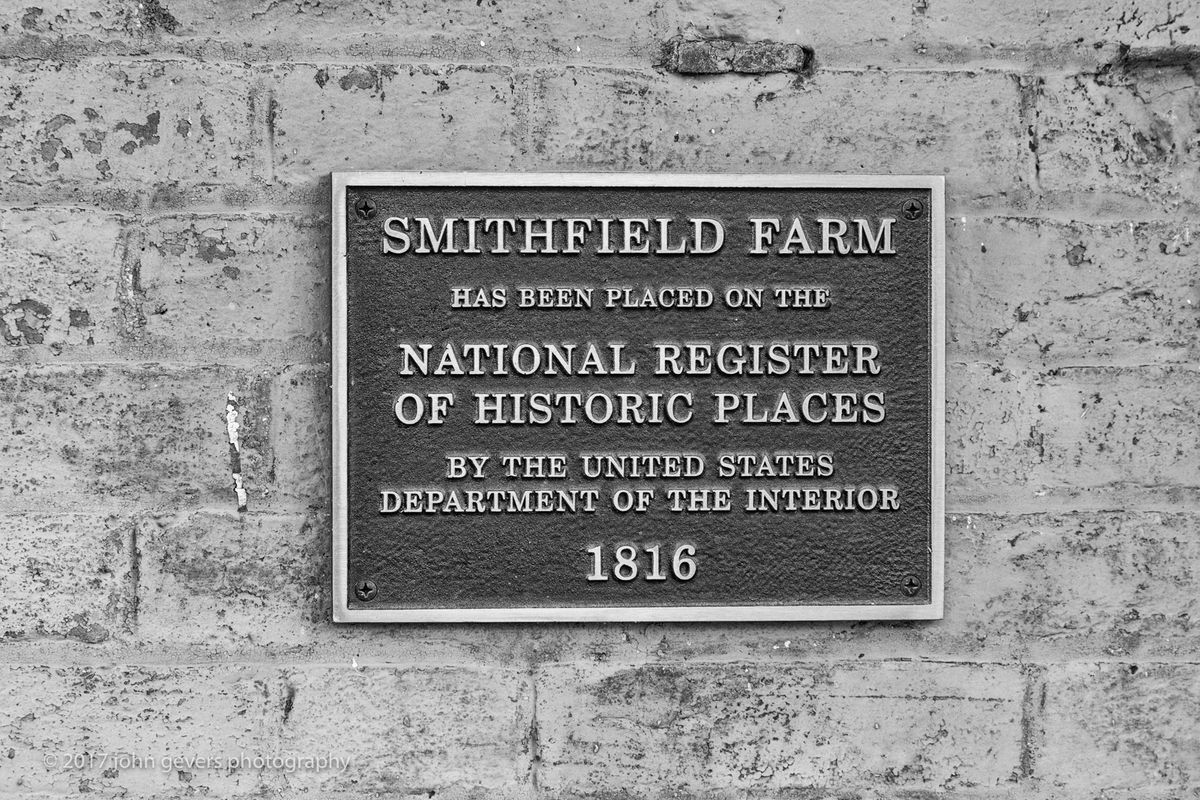

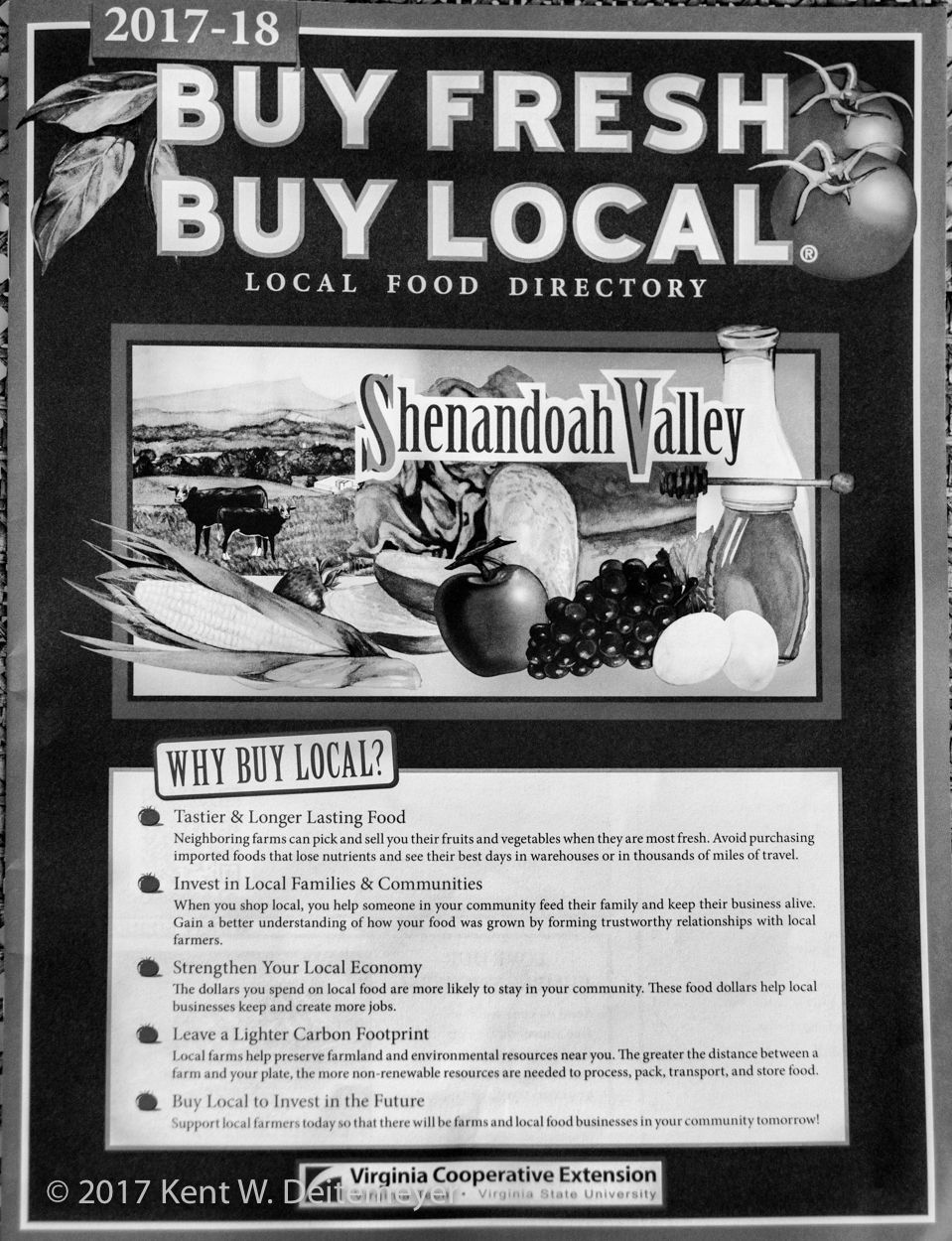

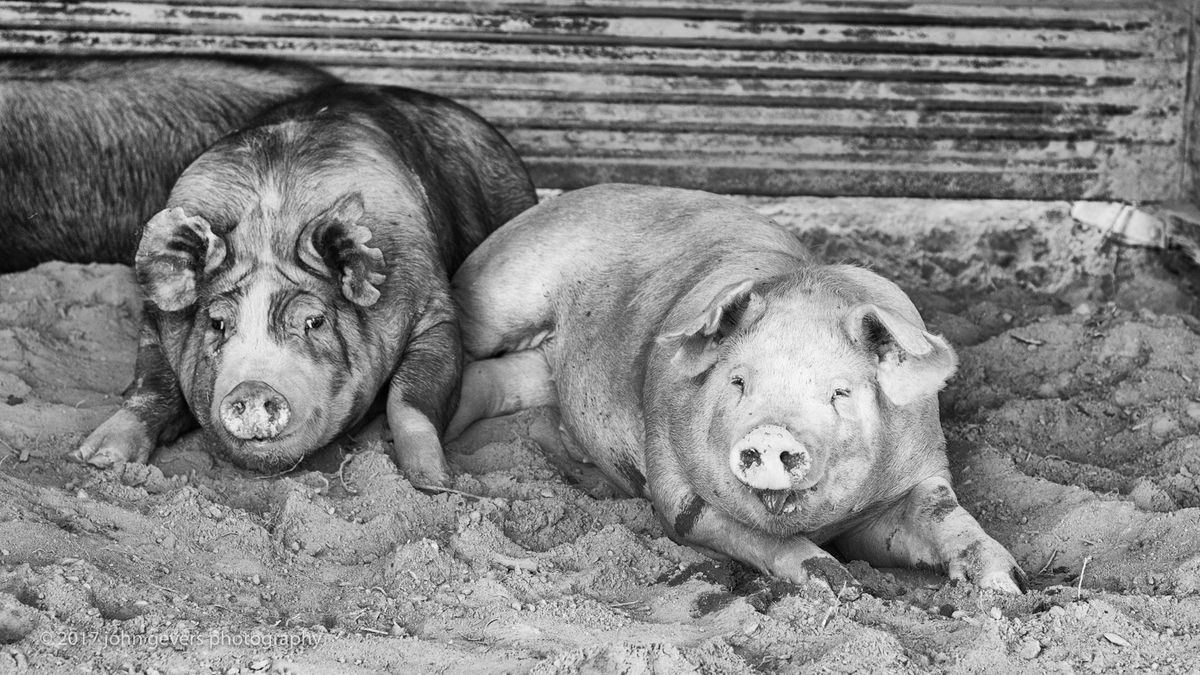

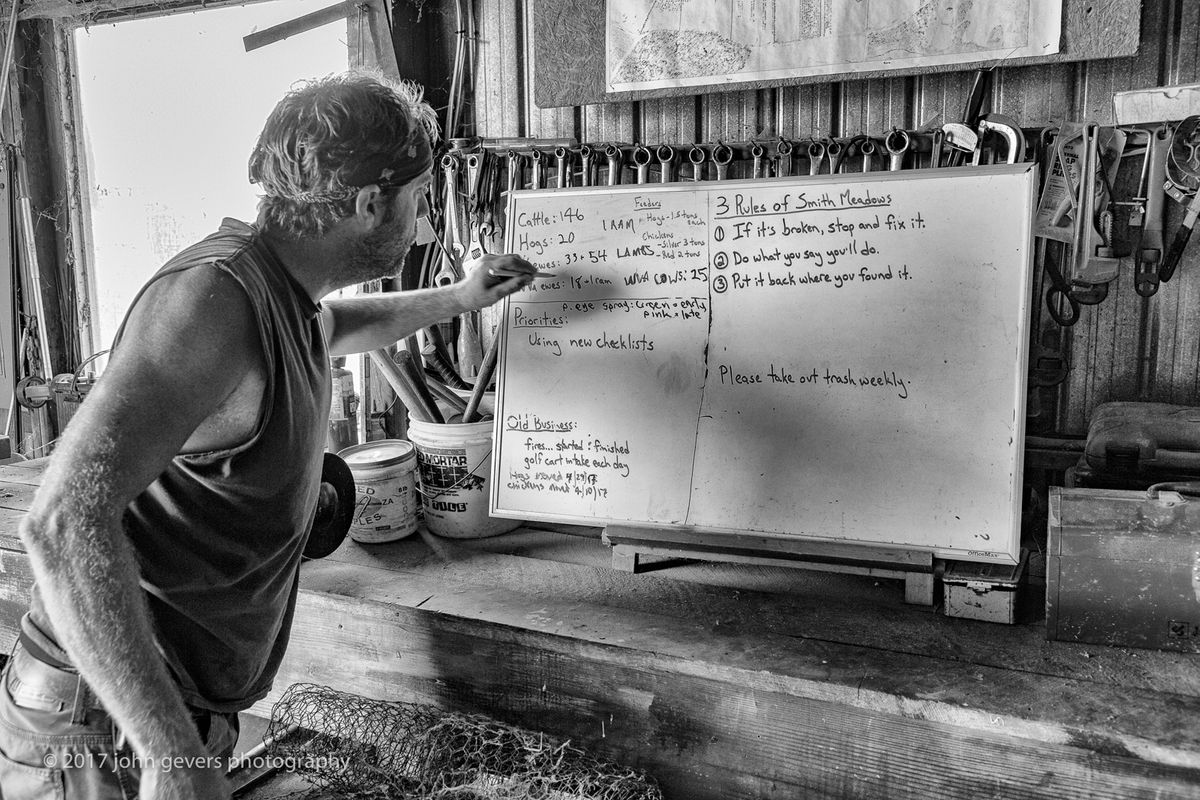

In the sweltering Virginia days of July, John and Kent met up in Virginia’s beautiful Shenandoah Valley and the Blue Ridge Mountains with a modern Aldo Leopold, Forrest Pritchard. We visited his farm, Smith Meadows, to experience firsthand his principles of husbandry and agricultural ethics in our quest to chronicle sustainable family farming.

Forrest is a noted author and lecturer on ethical, sustainable farming who practices what he preaches. His book, Gaining Ground: A Story of Farmers’ Markets, Local Food and Saving the Family Farm is a New York Times best seller. His second book, Growing Tomorrow: A Farm-to-Table Journey in Photos and Recipes garners five-star praises from editorial reviewers as “a down-to-earth look at how sustainable farming is changing the way we eat.” Forrest has become a leading light in the United States in the sustainable family farming movement and has proven how one can renovate a struggling farm, transforming it into a productive operation that produces healthy food for the local community.