Glenariffe Station • High Country Community

John Gevers and Kent W. Deitemeyer

Video of images above illustrates our story below.

Soundtrack: "Leave Where I'm From" • Tyler Stenson

Forrest Pritchard talks about the three “E”s of farm sustainability: Environment, Economics, Energy. Farmers tend to them equally as though three legs of the tripod that keep their farms humming along sustainably.

Care for the Environment includes managing soil to ensure on-going fertility and protecting streams from contamination.

Care for Economics includes making sure that income exceeds expenses.

And care for Energy includes tending to the farmer’s internal furnace – or passion – for farming. A passionate farmer is more likely to pass his or her farm down to the next generation, ensuring a legacy of sustainability.

Many of the high country sheep stations in New Zealand’s Rakaia Gorge have weathered generations of challenges to maintain sustainability. Four generations of Ensors have seen Glenariffe Station through deadly weather extremes, earthquakes, fluctuating prices for wool and lamb, heavy-handed government policies, ecological concerns about overgrazing, and mandates to retire the highest of the land in the stations back to the Crown (government).

Alastair and Prue Ensor took over farming Glenariffe from his father and grandfather in 1973, at a time when an army radio was needed to call in grocery orders.

“You could hear what others in the Gorge were ordering,” Prue recalls, “and when someone else ordered something particularly nice, you couldn’t help but wonder, ‘Oh, I wonder if so-and-so is going to invite us over for dinner next week?’”

The third generation Ensors began transferring operations of Glenariffe to their son and daughter-in-law, Mark Ensor and Belinda (BJ) Bull in 2002. Mark was working on a PhD but answered the call to return to the family’s farmstead, and so the fourth generation of Ensors took over daily operations in 2009. Mark’s mom and dad still live on Glenariffe in a more recently built home where Prue manages an extensive garden dug out of the steeply raked Alpine hillside. Alastair is a farm consultant and often uses his ultralight airplane from Glenariffe’s airstrip to fly to his clients from this remote part of New Zealand. He was an avid jet boater on the Rakaia River but sold his boat after a bout with cancer inspired him to pursue his dream of flying.

Mark and BJ now run about 4500 Romney sheep at Glenariffe with an aim of growing fewer sheep on the farm’s 2000 acres (809 hectares) but raising them to a greater weight each. The wool is destined for the carpet market but the international market doesn’t bring in what it used to. Income from the many lambs that debut each spring also suffers from the price set internationally, meaning that being a New Zealand sheep farmer doesn’t ensure sustainability like it once did.

Farmers today, especially in high country stations, have to work harder than ever to cover costs and remain viable. BJ and Mark also host numerous Standardbred race horses in one of their luxurious pastures for owners who need a place for their gee-gees to convalesce or retire. They also sell hay they make from the paddocks on Glenariffe’s terraces.

One of the ways the stations in the Rakaia Gorge keep their heads above water – even when the streams and rivers running through overflow from glacier and snow melt – is by maintaining a close-knit community. They look out for each other and support each other. For example, Mark also serves as the chief of the volunteer fire brigade that serves the entire valley, and a Rakaia machinery syndicate of nearby stations means that many share the expenses of machines that may only be needed once or twice a year.

There is a feeling of family amongst many of the Rakaia farmers, and, in fact, many of them do share bloodlines. It’s a vast Alpine region that requires accessing reservoirs of perseverance and hardy spirit to survive. The nearest town is 90 minutes down the winding shingle (gravel) road, and multiple streams must be forded along the way. Phoned-in grocery orders are delivered once a week, along with a week’s worth of mail. Medical emergencies are handled by helicopter or plane. Children must be bussed long hours each day once they reach school age – if there are even enough kids to warrant sending a bus into the remote area. Or parents must commit to home-schooling or choosing boarding school for their young ones.

Buildings, fences, bridges, and vehicles must all be built and maintained using materials hauled in from long distances. No mobile phone service penetrates the rugged landscape. When the landline or Internet – yes, Glenariffe and surrounding Stations are connected to the web – go out, it can take a while for the repair technician to appear.

It’s from the deep sense of community in the Rakaia Gorge that Mark and BJ appear to maintain their passion and energy. Well, that, and their children.

Ben (Benny), 3, and Charlotte (Charlie), 1, are the new generation of Ensors (Mark and BJ’s children) who know only this rugged, remote existence, and they appear as happy as you might expect from children growing up close to the earth, surrounded by animals, and with loving parents who work right outside the house windows.

Adoring Grandma and Grandpa (Prue and Alastair) live just down the lane a few minutes by foot – on the same farm. Life isn’t on the same rigid schedule that city life tends to be, and nothing needs to be sanitized. Growing up on a farm means your immune system is exposed to all it needs to be to function well, although the parents do wonder about the day when their kiddos interact more with others in the nearest town. Germs of the human variety are bit different than the animal variety.

Mark is an attentive father while managing the farming side of Glenariffe, but, of course, the domestic chores of running a sheep station are varied and many, and that’s where BJ shines. Isolation requires being organised since there are no shops or grocery stores nearby if you need something in a hurry. Everything needs to be ordered to make the weekly Friday delivery or it will mean taking most of the day to drive to Christchurch and back just to pick up supplies.

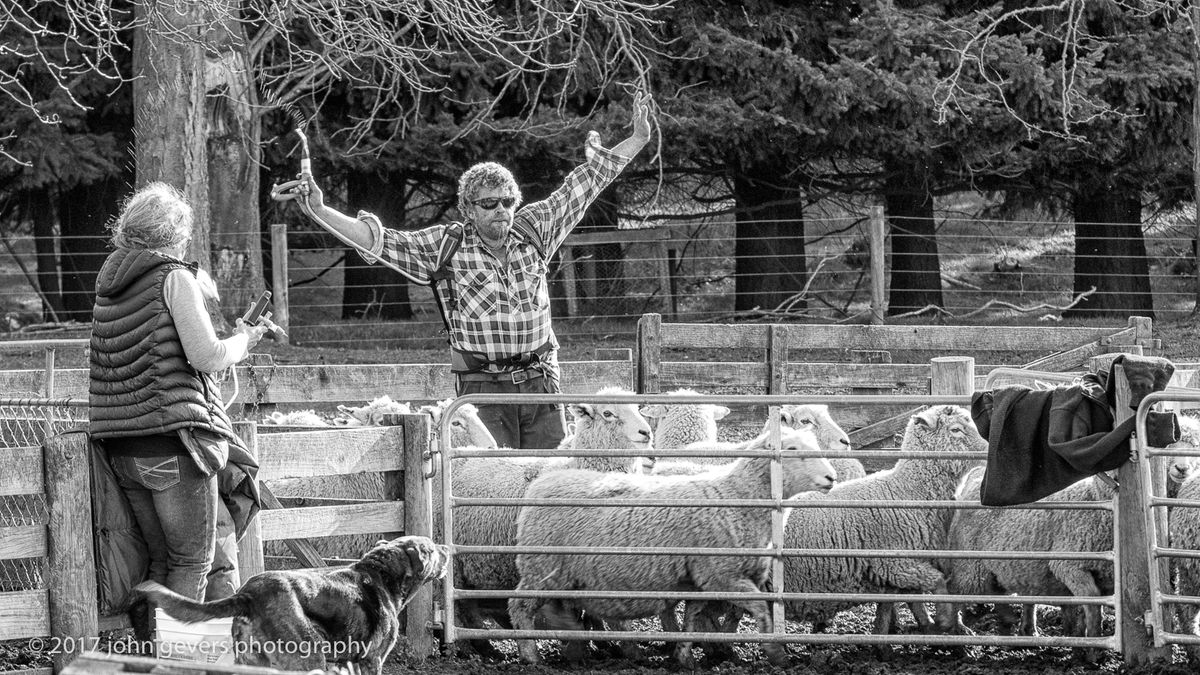

Looking after two young children keeps BJ busy but she also assists Mark with working the sheep as she did drenching the flock against parasites during our recent visit. When it’s wool shearing time, the shearing team needs to be fed three meals a day over a four or five day stretch. It makes for long days in the kitchen for BJ catering for the hard-working, hungry shearers.

As for the third leg of the sustainable farm tripod, the environment, five generations of Ensors have awakened each morning to the splendor of the Southern Alps. And they lay their heads down each night under darkness that encourages starshine to dazzle dreams. This is one family that doesn’t take humans’ and their livestock’s impact on the stunning landscape lightly.

For instance, Glenariffe has worked with New Zealand Fish and Game over decades to preserve an essential salmon spawning stream that flows through the station. Alastair, and now Mark, maintain riparian environmental fencing to minimize animal contact with the station’s water resources.

Sheep stations have long relied on dogs to help muster and manage large flocks of sheep, and Glenariffe and its neighbor stations are no exceptions. Pip, Drum, and Houdini are right there next to Mark and BJ as commands are shouted and the shepherd sounds his whistle. Pip, especially, bolts like lightening and seems to have an endless supply of fuel. The Ensor family includes multiple dogs – the outdoor sheep herding kind are cared for almost as well as Maggie and Amy, two Golden Labs that lounge about the interior living area as comfortably as we photographers were made to feel by the Ensor family.

Find us on Facebook @stewardsoftheheartlands